For the past ten years, I have spent a considerable amount of my free time exploring various cairn sites from Pennsylvania to New England and beyond, attempting to discover a pattern of design that might help to explain who constructed the cairns, and when. With many sites up for grabs as our society expands and wild lands become more threatened, the cairns and other stone constructions found on these lands are also at risk. Much has undoubtedly already been lost to development.

In 1997, when I began my study of the Oley Hills site in Berks County, Pennsylvania, I wanted to determine who constructed the impressive and unusual cairns, platforms, walls and terrace, and possibly their date. The previous owner had concluded that the stone features were Celtic, and archaeologists were pretty dismissive of anything constructed of stone, concluding the features were Colonial. I had many archaeologists visit the site, but relatively few were interested enough in it to help to understand it or even comment on it. In spite of this disinterest on the part of archaeologists, I continued to search for evidence, and in time came up with some information that in the future may help to save this site and others like it.

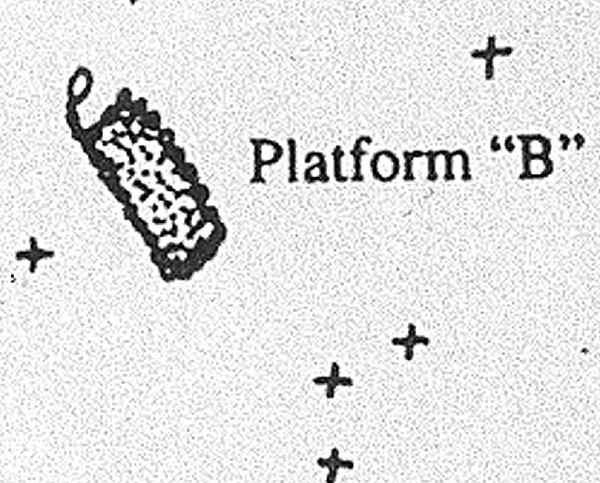

The following spring I had Bill Sevon, a geomorphologist with the Pennsylvania Geological Survey, visit the site with his wife. As we walked through it, I pointed out the various stone features. At the large boulder (Fig. A), which I concluded was the heart of the site, he remarked that the boulder was not a glacial erratic but a tor, which in this case was the highly weathered remains of a bedrock outcrop that had eventually eroded loose from the ledge it now sits on (Muller 1998, 1999). The last continental glacier, the Wisconsin, ended its southern movement twenty miles north of the Oley Hills site, which precluded any glacial erratics being found south of this margin. At one time, Bill said, the boulder probably rocked, and that the small stacks of rock under the north end of it were placed to keep it from rocking (Fig. B). Eventually large sections of the south end of the boulder broke loose and now form a semicircle of stone slabs underneath it.When that happened, the boulder lost its rocking abilities.

We then walked to the large inclined cairn (Fig. C), and there Bill pointed to four large quartz cobbles imbedded in the east face of the cairn (Fig. D. The quartz appears as light gray on the image ) and said that the quartz could not have come from the ridge where the cairn is located, since the ridge was composed entirely of a granitic gneiss with only a dike of diabase intruding into it. Furthermore, since the glacier stopped twenty miles to the north, any anomalous rock could not be attributed to glacial debris. Consequently, the quartz had to have come from a presently unknown location in the valley below where pegmatites are more common. This of course meant that the quartz was deliberately sought out and brought to the cairn site to be placed in the east facing side.Examining this process more closely, it is highly unlikely that that an eighteenth century German immigrant farmer would have done this. Yet because of the association of quartz in a ritualistic sense with the American Indian, the placement of quartz makes for a more logical interpretation of the cultural origin of this one monumental cairn and of others at the site.

Since then, I have sought answers from other sites to help understand and explain who constructed the manmade stone features found on them. In many instances, the information remains elusive, but for the Smith cairn site in Rochester, Vermont, the detailed deed information that we have for it, combined with a collection of ledgers or daybooks that were kept by Chester Smith, the farmer who worked the land from 1847 to his death in 1903, help to remove his name and other former landowners from the roster of those who might have been responsible for constructing the cairns, since there was no evidence in the daybooks that Smith built the cairns, nor is it likely that the former landowners did either. Some of this data I have laid out in the web article An Unusual Crescent-Shaped Cairn and the Significance of Quartz, (Muller 2007b).I believe that the repetition of certain stone features or accents from site to site throughout the Northeast is an indication of a region-wide cultural response to the landscape, and is highly unlikely to be interpreted or placed at the doorstep of colonial farmers if examined carefully and with an open mind. In fact, there is no written or documentary evidence that farmers constructed such large cairns as those found on sites in Vermont to enhance farm production; building them was exceedingly time consuming and makes absolutely no sense when farmers had trouble enough just trying to survive on upland farm sites.With regard to stone accents, I am thinking particularly of split-wedged boulders and the deliberate placement of quartz in striking locations in cairns.If we examine these accents from a regional perspective, they take on heightened significance.

By pointing out how similar features are found at sites many miles distant from one another, we then begin to weave a story that will help to undermine the paradigm still held by archaeologists in the Northeast that the Indians had no stone building technology until this part of North America was settled by Europeans in the seventeenth century. Many out there, such as Peter Waksman, Larry Harrop and others, have assembled data, photographic and otherwise, that will help to form a new prehistory of the region.

The study below of a site in Stockbridge, Vermont, should be viewed as just one more piece of the puzzle. I have noted where necessary how certain distinctive features have been found elsewhere at sites from Pennsylvania to southern Vermont, thus emphasizing the regional nature of this phenomenon. Besides being fascinating in their own right, they also make for a compelling story.

Of the half dozen or so major cairn sites in Vermont, the one in Stockbridge, near the border with Barnard, is among the most intriguing, probably because it is one of the least known and explored, and seems to hold considerable potential.

Located on the side of a mountain off Perkin's Brook, about a mile hike in on a logging road, it was first explored by Ernie Clifford, a Vermont native, about ten years ago, who had heard about it from a hunter friend. Ernie then showed it to me one beautiful April morning four years ago, at which time I took some photographs of two of the largest cairns but didn't spend much time exploring the area. 2003 was the year when I was first introduced to the major cairn sites in Vermont by Ernie, and I was simply doing a lot of looking, and documenting as many sites photographically as I could. But as I began to be more familiar with certain types of cairns and paid greater attention to how they were constructed and located in the landscape, I thought back on the Stockbridge site and how little I really knew about it. Upon reflection, it seemed to be very important with respect to the other sites I had seen, particularly how certain cairns seemed morphologically similar to others I had seen elsewhere, and I was determined to have a much closer look at it and probe the woods around the site.

On September 21, 2007, Ernie agreed to guide a small group of four to the site. We met at a parking spot at the beginning of the logging road, and then walked up a steep slope by switchbacks to a nearly level area that had been recently logged. Here the road split: the more recently used road veered to the right and eventually past a foundation and underground chamber of an old abandoned colonial farm. Instead we went straight ahead on an abandoned spur that was slowly being swallowed up by trees and shrubs on either side. After about ten or fifteen minutes of easy walking we were supposedly in the area of the cairns, at an elevation of 1600 feet. Four years ago, one beautiful April day, I visited this site when the trees and bushes had not yet blossomed, and I could make out some of the stone cairns from the road. But now, in late summer, the dense foliage obscured everything beyond a few feet. Ernie, however, knew just where to enter the woods, and after some easy bushwhacking we were at the first large structure in a pine grove.

Approaching it from the south, the cairn didn't look like much. Young saplings had fallen against the south end of it, which sloped gradually to the ground, and some stones had been knocked out of place by repeated tree falls. As we walked counterclockwise to the north facing side, the construction was less disturbed and impressive looking (Fig. 1). Here I was impressed by the intentional directionality of the well constructed face of the cairn as opposed to the other side. I had seen this before at Parker Woodland in Coventry, Rhode Island, where five different cairns had their well constructed side facing east. The Stockbridge example faced north, and I am at a loss to explain this, as I am the large cairn with the quartz cobble (see below), which also is north facing.

The cairn was roughly rectangular in shape with its axis oriented east-west. It measured 10.7m long, 2.3m wide and 1.4m high (35' x 7.5' x 4.5'). Some balsams and hemlocks perhaps thirty to forty years old had fallen against it, criss-cross fashion (Fig. 2). This was not a benign looking environment. The ground was uneven and characteristic of 'pillow and cradle' topography that Wessels (1997) describes as being caused by periodic tree blow-downs over a long period of time; there was no evidence that this area had ever been cultivated, although by the size of the trees in the area, tree harvesting had definitely occurred only decades before.

The stones comprising the cairn appeared to be local schist that cleaved in broad horizontal planes that permitted easy stacking. Considerable lichen and moss growth had formed on the surface of some exposed stones on top, which compared quite favorably with the thick mats of moss that a group of us had seen on five cairns near the summit of Glastenbury Mountain in southern Vermont (Fig. 3), which we concluded predated the construction of the fire tower and Long Trail to the summit between 1913 and 1930. On the east side of the cairn was a short extension or 'tail' with a diagnostic cobble of quartzite on top (Fig. 4) that reminded me of similar stone extensions to some cairns at the Smith cairn site in Rochester, Vermont. There, some of the extensions seemed to reach out to connect with springs that flowed in wet seasons (Fig. 5), but here there was no apparent water source.

I have no idea why this large cairn and the others were built. To me, they are monuments of some kind, although this is only a hunch and is not based on any factual evidence. It is obvious, though, that considerable effort went into gathering and then piling the stones, which may have required a team of workmen, especially to move especially large stones that must weigh hundreds of pounds, especially the one to the far left in Figure 1. But where did the stones come from? There are no concentrations of loose stone on the ground in the area, and the terrain in the vicinity of the cairns does not look as though it was ever tilled, which was the main means of forcing stones to the surface through frost action. Without tilling, stones will stay put in the ground. So the source of the stones remains a mystery.

A bit further to the north, and in a depression near the cart path, nearly out of sight, was an impressive, slightly wedge-shaped cairn as seen from the side (Fig. 6), which as one went around to the right, presented a tightly constructed fa'ade (Fig. 7). I vaguely remembered this cairn from my first trip to the Stockbridge site, but now I was able to measure and record it photographically. It was 2m wide by 1.5m high (6.5' x 5').

From there we walked north along the cart path to the bottom of a pine knoll, at the base of which was a terrace-like construction of stones measuring 2.6m long by l.5m high by .8m high (8.5' x 5' x 2.6') built against the slope (Fig. 8). Above this construction, and on top of the knoll, was a large cairn (Fig. 9). The combination of the small terrace construction and the large cairn reminded me of similar arrangements I had seen at the Smith site in Rochester, such as this small cairn at the base of a knoll, above which was a terrace wall surrounding a low stone mound (Fig. 10). This arrangement and juxtaposition further emphasized the directional orientation of the features and how one should approach them: both examples were much more impressive if seen and approached from below.

The large cairn on top of the knoll measured 5m wide by 6.3m long by 1.9m high (16.4' x 10.6' x 6.2') and was distinguished by having a large, round quartz cobble placed directly in the middle of the north face (Fig. 11). This was no accident, and the use of quartz here and in other features on the site implies a cultural significance quite apart from any Colonial or European association (Muller 2007b). At the southwest corner of the cairn was an extension or 'tail,' about six feet long, that ended at a large horizontal stone slab (Fig. 12).

We had seen most of the major features at the site, but I felt we were just scratching the surface. Several of the others wanted to see the chamber about a quarter mile away, but I wanted to explore more around the large cairn. Before we split, a few of us walked down the slope to the west from the large quartz accented cairn, where we encountered a handful of other manmade features. One of them was a low rectangular construction with several quartz pieces on top (Fig. 17). And further to the south on the same slope was an impressive horizontal cairn on the edge of a rock outcrop (Fig. 18).

Walking back to my car, I looked for another large cairn in the woods that I had seen several years previously, and I eventually found it obscured by a thick tangle of briers and brush in a dense pine grove (Fig. 22). This cairn measured 5.3m long by 2.7m wide by 1.3m high (17.3' x 8.8' x 4.2') and it had quartz cobbles intentionally clustered in the southeast corner (Fig. 23).

Cairns were placed at a site for a reason. In some cases, and with patience, one can discover what attracted the cairn builders in the first place. Often it was some natural feature in the landscape that had phenomenal attributes, such as the limestone outcrop at the Peterborough, Ontario, petroglyph site, where the limestone is fissured and water can be heard flowing underneath (Vastokas and Vastokas 1973: 49). At a site in Hackettstown, New Jersey, it was a beautiful waterfall that must have attracted the builders of the six or seven large barrel-shaped cairns. At a large cairn site in Hallstead, Pennsylvania, it was a ritualized spring (Fig. 24) enhanced with two lintels and support stones, that seemingly provided the impetus for the construction of more than 100 large and beautifully constructed cairns (Fig. 25). At the Oley Hills site in Pennsylvania the focus was a large erratic-looking boulder (Muller 1999. See also Fig. A, above), and at the Smith site in Rochester, it seems that the prevalence of springs and the east facing slope were the main reasons why 150 plus stone cairns and other manmade stone features were placed there (Muller 2007b). These are some of the most obvious examples.

But the Stockbridge site does not easily reveal its secrets. It, like many other sites, probably started with the construction of one cairn in response to some distinctive natural feature or a phenomenal characteristic in the landscape, but that has yet to be found. Over a period of time, other stone constructions were added, so that like the skin of an onion, these added elements obscure the original core. By determining the extent of the site, and by approaching it from different directions at different times of the year, the single feature or characteristic that stimulated all this attention might eventually be discovered.

In October 2010, I returned to the Stockbridge site with Dave Connelly, a friend. I showed him the cairn with the large quartz cobble (Fig. 11, above), and from there we headed west, down slope, to a small valley with a prominent ledge outcrop (Fig. 237). From there, we could look behind us to a long, stacked stone cairn on a ledge outcrop (see Figs. 18 and 21, above), probably 30 feet above where we were standing. I had not examined this cairn closely before.

Dave decided to have a closer look at this cairn and he took off alone up the slope. When he reached the top, he motioned to me to come up to have a look. On top of this flat-topped cairn were three shaped and tapered recumbent standing stones, the largest being about a meter long, and with a flat base; the two others were slightly smaller but also had a flat base (Fig. 1406). Apparently, they had once stood upright and were perhaps ‘killed’ when the site had lost its function. This cairn overlooked the ledge outcrop below, which obviously had ‘phenomenal attributes’ that Jack Steinbring referred to in his 1992 article (Steinbring 1992).

Muller, N. E., Early Stone Cairns and Rows in Eastern Pennsylvania 1998.

Muller, N. E., Stone Rows & Boulders: A Comparative Study 1999

Muller, N. E., Vermont Platform Cairns 2003

Muller, N. E., Delaware Water Gap 2007

Muller, N. E., An Unusual Crescent-Shaped Cairn and the Significance of Quartz 2007b

Muller, N. E., Fahnestock Memorial State Park 2007c

Steinbring, J., Phenomenal Attributes: Site Selection Factors in Rock Art, American Indian Rock Art, 17: 102-113, 1992

Vastokas, Joan M. and Roman K.Vastokas, Sacred Art of the Algonkians: A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs, Peterborough (Ontario), 1973

Wessels, Tom, Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England, Woodstock (VT), 1997

Copyright 2007 by Norman E. Muller